Students on Ice / WWF-Canon

After more than 24 hours Melville Bay, where the Arctic Tern was accompanied only by guillemots and icebergs, we started to see land in the morning. And in the afternoon we landed by Savissivik, a small community of 74 people on the edge of the Melville Bay. We anchored by the settlement and put the zodiac in the water, carrying Sascha and I to the village to talk with the local hunters and Tim and Thorsten to check out a potential salt marsh site.

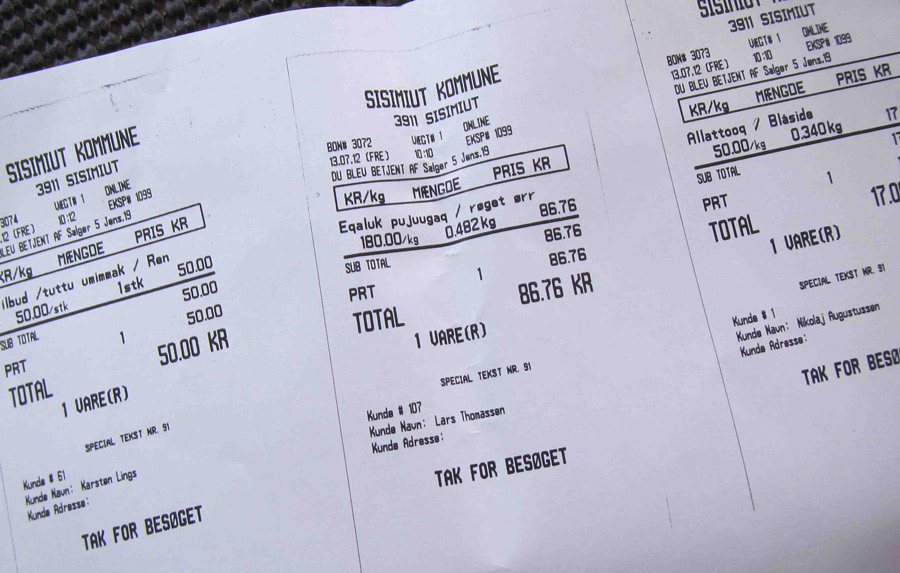

Sascha and I went to the local Pillersuisoq, where groceries can be bought. We met a hunter from the community, who told us that they just recently had their first supplies of goods and that a second ship was to arrive in September. These supplies were to last them all winter and well into the summer next year.

Students on Ice / WWF

But Savissivik is a hunters’ community and most people here live on what they hunt themselves. Hides of polar bears were hanging outside to dry and seal blubber was let on the stones for the dogs. On a warm summer day the dogs looked anything but pleased with the long wait for snow and sea ice.

We were told that hunting of seal, narwhal and beluga whales as well as polar bear is the predominant activity. Quotas for hunting of many species are set by the Greenland Government, and the hunter explained that the season for hunting of polar bear is short – often the 18 bears harvested locally are taken within the first few months of the season. While the communities further south seemed to live off both hunting and fishery, there is no fishery here yet. Changes in climate may however lead to the introduction of Greenland Halibut fishery here too.

By the harbor we met another hunter, who told us about life in the settlement. He explained that there are currently 74 people living in the settlement. We saw a number of abandoned houses so this community must have been bigger not so many years ago. The hunter also explained how they would harvest Little Auks from the cliffs behind the settlement by waving nets in the air.

Two kids were playing with dogs outside a house. We asked them about their school, and they explained how the local school ends after the 7th grade. Children must then move to Qaanaaq for further schooling.

We met up with our hunter again, building a new kayak. He explained how everything was made from wood and skin, and how he tied the pieces together using string. This makes the kayak flexible and easy to repair during hunting.