The Laptev Linkages crew. © Alexey Ebel

A WWF-led research team, a Canon photographer, and crew are traveling to Siberia’s Arctic coast on the Laptev Sea,

to help solve a scientific mystery. The Laptev Linkages expedition is sponsored by Canon.

Today, the crew answers your questions.

Gillian asks: What’s the purpose of the expedition?

Tom, our walrus expert, explains:

[youtube clip_id=”zXQEQV9APzM”]

Joshua asks: What has your research revealed so far on the expedition? Anything that stands out?

Polar bear at a walrus haulout. © Alexey Ebel / WWF-Canon

We won’t know the answer to the genetic puzzle for a while, because we’ll need to send our samples to labs for processing. However, we are making some interesting observations. Geoff says: “We encountered around 400 walruses gathered on a sandspit – likely the largest number of walrus recorded at this site in many decades, possibly ever.”

Barbara asks: How cold is it there right now?

The Arctic does get above freezing in the summer, but August can already be quite cold. Expedition member Tatiana is from Murmansk, Russia – the largest city in the Arctic. Even she is finding it chilly: “Being from northern Murmansk, it seemed absurd to me to take real winter clothes for an August trip. But it seems that I’m the one who was absurd. My snowmobile gloves and hat aren’t enough – the temperature generally doesn’t reach 1C. But despite these minor annoyances, I am very pleased with the experience.”

Hazel asks: I often hear about the threat to their survival as the ice retreats more quickly every year. How serious is the problem, for both polar bears and walrus?

Tom says: Sea ice loss is a clear and present danger to all life that depends on ice. Both polar bear and walrus depend on the ice as a platform to rest and feed. They’re expected to reduce in numbers, and to be found in fewer areas in the future. The reduced ice also means an increase in human activities in the Arctic like shipping and oil and gas development, which threatens these species even further.

@skootzkadoodles asks: Are walruses as threatened by climate change as other seal populations?

Yes – walruses often rest on ice, but when ice is unavailable they must congregate in larger numbers on land. They quickly exhaust nearby food, and have to travel longer distances to feed – this can be stressful. In addition, a large group of walruses can panic and stampede if disturbed by a predator, and some can be crushed to death.

Donald asks: Can’t polar bears hunt from land? Not that I’m happy about shrinking ice sheets, but is it impossible for them to adapt?

2 kilograms

The amount of fat a polar bear eats each day

Tom says it all comes down to calories: “Polar bears are highly specialized carnivores and require a significant amount of calories from animal fat to thrive in the tough Arctic environment. Fat comes mainly in the form of seals, which depend on sea ice.

Individual bears do feed opportunistically on carcasses, vegetation, eggs, and fish, but there aren’t nearly enough calories in terrestrial fare to sustain polar bear populations in anything like present numbers.

We also have to remember that the current rate of change is unprecedented in the history of today’s mammals. While some populations are likely to adapt new strategies, like spending more time fasting onshore, it is unlikely that true evolutionary adaptations in feeding ecology or physiology would be possible.”

Jasmine: Are the walruses and polar bears in the Laptev safe from oil spills?

Tom says: Oil exploration is still low in the Laptev Sea. The most likely spill would come from a ship – as summer sea ice decreases in this area, we’re seeing a big increase in commercial shipping north of Russia, through what’s called the Northern Sea Route.

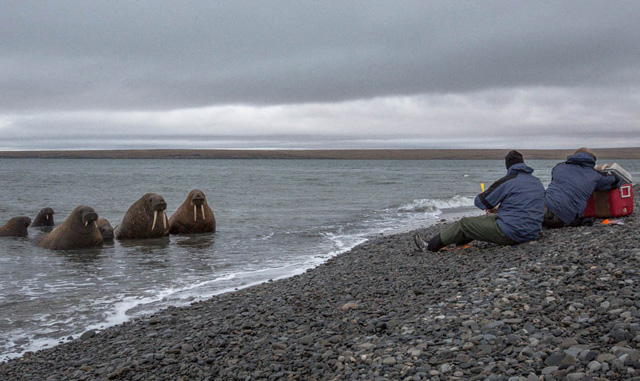

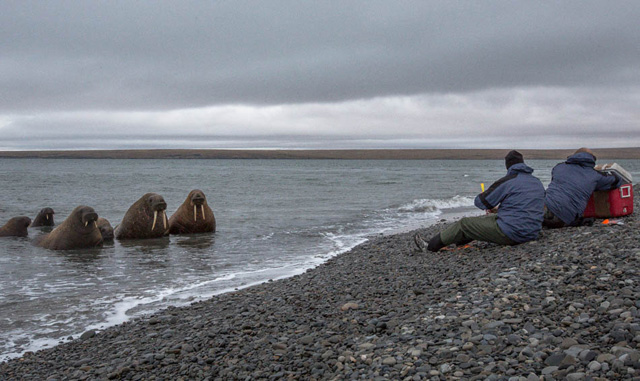

Cameron and Karen ask: Are the walruses frightened if you get close?

Geoff says: “Walrus spook easily and can stampede into the water- the last thing we want to happen. When we took genetic samples this weekend, we were lucky – the winds were favorable, carrying our scent out to sea and away from the group, allowing us to eventually creep within 30 meters.

Watch a walrus stampede captured in 2009 (starts at 0:32):

[youtube clip_id=”IA-_QsCEZ0U”]

@buddhasloth asks: How do one become a researcher or an assistant on one of your expeditions?

On our Arctic expeditions, the researchers range from students working towards an advanced degree in Arctic field biology to established Arctic biologists. But even if you aren’t studying the Arctic, WWF-led trips to the region are available. Check out the trips offered by WWF’s office in the United States or contact your local office to learn more.